In the bustling streets of early 16th-century Italy, merchants and scholars crossed paths in vibrant marketplaces. Among them walked Luca Pacioli, a man whose curiosity for numbers matched his faith in order. In 1522, Pacioli unveiled his seminal work, “Aritmetica.” It was more than a book—it was a beacon that illuminated the secrets of arithmetic, practical mathematics, and the intricate art of accounting.

This treatise did the unthinkable: it blended the merchant’s needs with the precision of mathematical principles. With it, Pacioli laid the blueprint for double-entry bookkeeping, forever changing how traders, banks, and cities managed their fortunes. Soon, whispers spread, and he became revered as the “father of accounting,” a title that still rings true today.

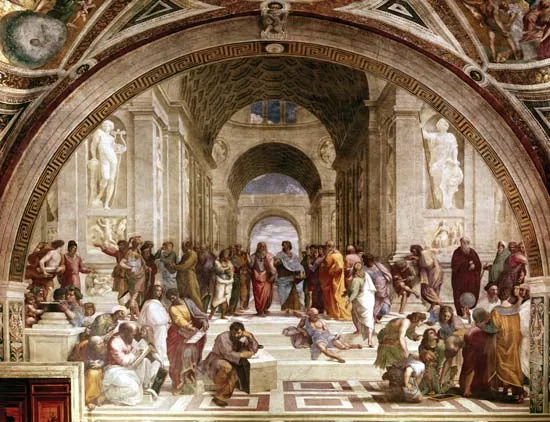

Yet the story of numbers didn’t start there. Mathematicians across Europe dusted off the works of ancient masters—Euclid, Archimedes, and their peers. Renaissance thinkers, fueled by fresh translations and boundless curiosity, unlocked the geometric puzzles and clever devices of these classical scholars. Each theorem rediscovered became a new brick in the foundation of Renaissance knowledge, reminding the world that progress often begins by standing on the shoulders of giants.

The sea called, and so did the promise of adventure. As daring explorers readied their ships, a quieter preparation was underway. Trigonometry—the language of triangles—emerged as every navigator’s secret weapon. Whether charting a course to mysterious continents or aligning the sails with shifting winds, these mathematical tools made the impossible possible.

With each journey, mathematics was at the helm. Calculations guided new trade routes that would reshape economies, and every successful voyage was a testament to humanity’s ability to merge curiosity with calculation.

Not all Renaissance heroes brandished equations. Joseph Justus Scaliger, a scholar with a passion for order, dedicated himself to arranging the epochs and events of history. Through his innovations in chronology and his influence on early statistical methods, Scaliger wove together the threads of numbers, stories, and time. His efforts revealed that mathematics was not only a tool but a universal language—one that could bring structure to chaos and bridge distant disciplines.

As the 1500s drew to a close, something remarkable began to stir. Scholars experimented with graphical representations—sketching out the first visual echoes of mathematical ideas that, centuries later, would blossom into modern charts and graphs. Though fledgling and sometimes overlooked, these early attempts hinted at a future where even complex relationships could be made clear at a glance—democratizing knowledge in ways unimagined before.